People ignoring Covid restrictions is disappointing, but not surprising—after all, we’ve seen this before.

It’s common now to see pictures like this flagrant violation of mask policy in a hospital

Jim Mone (AP) – Mike Pence deliberately and flagrantly violating mask policy at Mayo Clinic (2020).

or this crowded Alabama beach

or these images of poor mask compliance by adults

Unknown Photographer – Improper mask usage in an airport (2020).

or this image of a Georgia high school on its first day back in session, where there were reports of physical altercations over masks! (A week later, the school was shut down for two days of cleaning, following nine positive tests for Covid [5].)

Hannah Watters – Hallway between classes, first day of class, at North Paulding High School, Georgia (2020).

We often wonder how people could be so cavalier with a worldwide pandemic. Why would a small change in comfort override someone’s concern of long-term health risks for themselves and those around them? This question is at the core of what it means to be an Epidemiologist and a Data Scientist.

COVID-19, or Covid, is an intensely infectious disease with one of the widest ranges of symptomatic severity of any human virus. Covid is too new for us to calculate its infection rates and death rates. All we know for sure is they are alarmingly high. But the death rate isn’t the only concern. It causes long-term health problems too.

Covid is best known for harming the lungs, like smoking and pollution, but, like smoking and pollution, Covid harms more than just the lungs. Covid harms the kidneys, heart, arteries, lungs, liver, blood, eyes, and many other organs. The list of conditions it contributes to is longer than your arm: stroke, heart attack, seizures, deep vein thrombosis, diabetes, vision loss, arthritis, neuropathy, leukemia, loss of feeling in the fingers and toes, loss of motor function, and so on. In many people, these effects are quick to surface, and in many others, they will not surface for a long time.

Reverberations of Covid-caused organ failure will have long-lasting effects in every nation in the world. Millions of survivors who seem healthy now will experience organ failure and chronic disease ten, twenty, even thirty years from now. As we have dashboards today that show excess deaths attributable to Covid [6], in the future we will have studies which show major increases in incidence and severity of organ failure and chronic disease also attributable to Covid. Millions of people in their twenties who contract Covid—even asymptomatic survivors—will live into their seventies, eighties, or nineties, and their Covid-related complications will add to the healthcare burden. We will have healthcare burdens from now until 2090 because of Covid infections today. Make no mistake: this is a looming global crisis. We can’t yet fully anticipate the long-term effects on our healthcare system.

Reducing symptoms of Covid infections will reduce that burden. For example, a smaller insult to one’s kidneys today makes it less likely they will fail later. One can reduce symptoms of Covid by taking steps to reduce the severity of a possible infection. The primary means of this is reducing the viral load in the event of an exposure, by wearing a mask and staying away from strangers. In short: wearing a mask today will reduce healthcare costs in 2090. As data scientists, we will deal with these problems in the future. How do we convince people of these problems today?

Ironically, millions of people steadfastly refuse to wear a mask. There are no clear answers to why. Some of people’s perspectives are in the video above: some have come-what-may attitudes, some prefer to maximize their business’s profit, some are willing to take the risk of a fatal infection, some are willing to pass an infection to others. There is propaganda involved—media personalities that some people trust have said wearing a mask is unnecessary, so those people believe it is unnecessary (or hide behind the excuses they saw on TV).

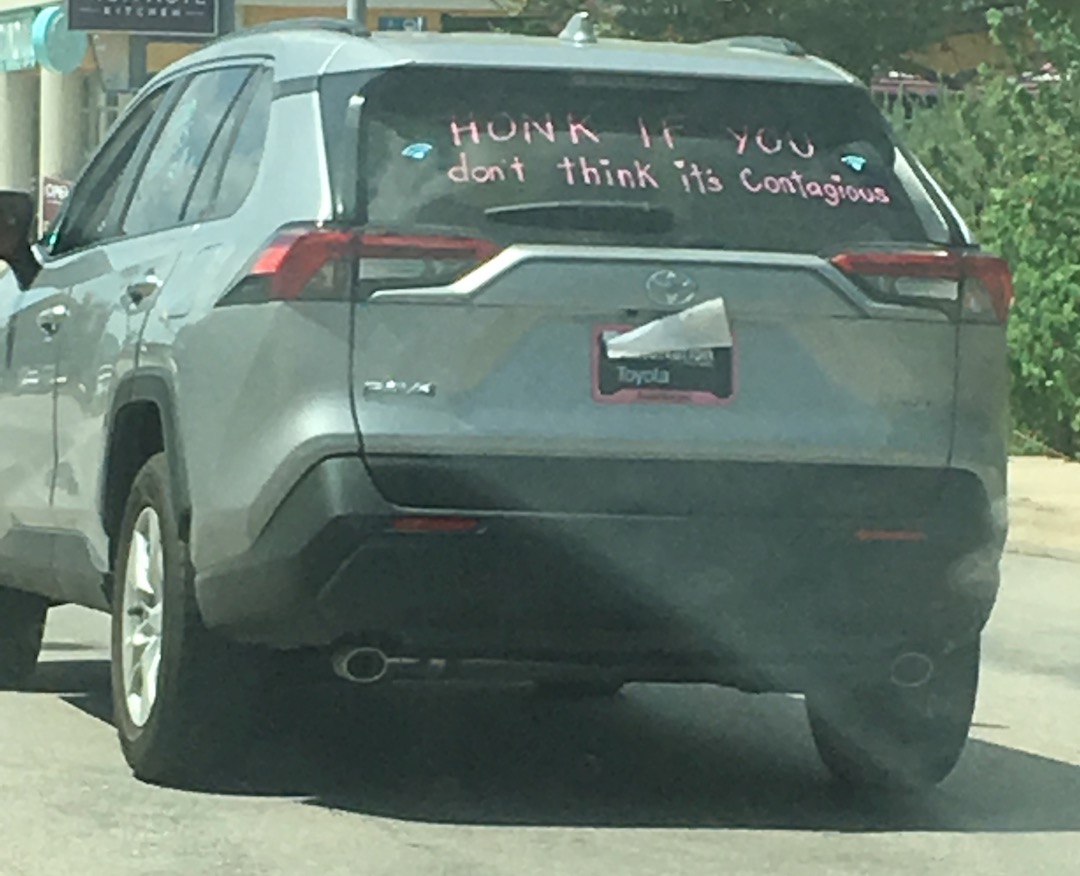

Fred Nugen – Car seen in Austin, TX (2020)

From an individual’s perspective, immediate and visible negative impacts (e.g., death) are a rare occurrence, and subject to many other factors out of the individual’s control. An individual will likely not see the direct impact of their choice to ignore mask policy.

People who ignore public health policies look at things from an individualistic perspective: they feel it should be their choice, not the government’s, whether to care about spreading disease. Unfortunately, an individual’s perspective does not take into account consequences that are distant—distant in time or distant in space. Individuals are notoriously bad at foreseeing or imagining long-term negative consequences in the face of short-term reward. Individuals are bad at denying themselves a small, but certain, short-term reward for a larger, but less certain, payoff in the future. Individuals are not good at this kind of risk assessment, and have difficulty avoiding long-term adverse effects. In fact, there is significant research showing how bad people are at postponing rewards and assessing risk. Furthermore, Individuals cannot measure societal impact—only large-scale coordinated teams of specialists can.

But from a public policy perspective, mandating masks for millions of people has a direct effect of saving thousands of lives. People who set mask policies look at things from a national, or even supranational, perspective. This is a core of epidemiology. Epidemiologists pull data from an entire state or country. Based on predictive models, they can detect trends that are not possible to see from within a smaller community. They can see how tiny changes on an individual level can multiply to the benefit the entire society. For example, they ask millions of people to take a specific action so thousands of lives can be saved. This is the kind of insight that is beyond the perception of a lay-person. As data scientists, and data science instructors, we must find ways in which to understand public policy and data-driven decisions.

It brings us to the following twist on a classic joke, by the San Francisco bar DNA Lounge:

An ER doctor, an epidemiologist, and a scientist walk into a bar. Just kidding, they know better.

A major part of public health policy is the outcome of policy recommendations—how much compliance there is, how effective the response has been. What we are seeing today with Covid is that voluntary compliance has been widespread, but insufficient. It will take a significant uptick in compliance for us to contain the spread of Covid down to isolated outbreaks.

Seeing people ignore Covid restrictions is disappointing, but not surprising—after all, we’ve seen this before, with smoking.

About 15–30% of the world smokes cigarettes at a rate of about 10–20 cigarettes per day (or half-a-pack to a-pack-a-day) [8]. Smokers smoke despite knowing it carries health risks. They smoke despite a century of deaths and data concerning the health risks of smoking, both to the smoker and the people around them. They care less about future statistical possibilities than present realities.

Wearing a mask is sort of annoying, similar to not having that cigarette you crave. But is this cigarette the one that gives you lung cancer? Is this cigarette the one that causes someone else’s heart attack? Probably not. What about two cigarettes? Probably not. But two million? Probably. Nationwide statistics are extremely hard to conceptualize at an individual level. Mask-wearing is really not that different. Some people find wearing a mask annoying, and they don’t wear one, regardless of statistics.

Each individual consciously makes a slightly suboptimal health choice for themselves, like having an extra bite of dessert, or going to a crowded beach during a pandemic. They take a calculated risk. When hundreds of thousands or millions of people all take the same calculated risk, it magnifies the negative consequences.

We see this in many arenas: Uber drivers routinely break the law and block traffic for “just a second.” For the personal benefit of their riders, they sacrifice everyone else’s use of that roadway, and unabashedly so. Doing that once or twice is hardly measurable. Multiplied by hundreds of drivers per city, day and night, and you get measurable traffic jams: “Ride-hailing services such as Uber and Lyft accounted for approximately 50 percent of the rise in vehicle congestion in the city between 2010 and 2016, according to a report released by the San Francisco County Transportation Authority” [9].

These are fragile systems not designed to be suborned on a massive scale. It’s the Tragedy of the Commons, that individual actions eventually add up to create a societal crisis. But people are rarely moved by the Tragedy of the Commons. Social pressure, and financial burden are more successful incentives for change.

Enforceable legislation changes behavior. Its effects aren’t always immediate, but it does effect change. With smoking, banning smoking in bars didn’t immediately result in every bar being smoke free. But many bars were, and slowly, others followed suit. And reducing smoking in bars does have an immediate positive benefit: In Chicago, the number of heart attacks in nonsmokers—nonsmokers—dropped by half within six months! [10] Even unenforceable legislation changes behavior. The University of Texas at Austin declared itself smoke-free, and compliance was voluntary and the policy was effective. (It didn’t induce 100% compliance, but it made a huge difference.)

For both smoking and Covid restrictions, we can issue guidelines and recommendations for a moderate, variable amount of success.

But, judging from the pictures and video above, to achieve a high rate of compliance with recommendations, we will need to enforce compliance with mandates and fines. It will take tremendous legal and social pressure from a wide variety of sources to achieve compliance to contain this virus.

Paul Sancya (AP) – Man pulls down a mask to smoke (2020)

Sources

[1] Jim Mone (AP), Mike Pence at Mayo Clinic, from https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/04/28/847570879/pence-responds-to-critics-after-not-wearing-face-mask-at-mayo-clinic (2020).

[2] CNN Now This, Brief interviews with Alabama beachgoers during COVID-19, from https://www.youtube.com/embed/jUNEFJ5WqgI (2020).

[3] Unknown Photographer, Poor mask usage in an airport, from https://i.imgur.com/N8Ny5oE.jpg (2020).

[4] Hannah Watters – Hallway between classes, first day of class, at North Paulding High School, Georgia (2020), from https://i.redd.it/sp44ts8rize51.jpg

[5] WSBTV, “North Paulding High School to shut down for two days after reporting 9 COVID-19 cases” (2020).

[6] World Health Organization, “World Health Statistics data visualizations dashboard – SDG Target 3.a – Tobacco control” https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.sdg.3-a-viz (2018).

[7] Fred Nugen, A car in Austin, TX (2020).

[8] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19 (2020).

[9] San Francisco County Transportation Authority Transportation Network Companies and Congestion Press Release Final Report (pdf) Teresa Hammerl, “Uber, Lyft main reason for increased traffic congestion in SF, study finds” (2018).

[10] TK: Chicago bar smoking regulation effects

[11] Paul Sancya (AP), Man pulls down a mask to smoke (2020), from https://static.euronews.com/articles/stories/04/65/80/06/773x435_cmsv2_4fff541e-0f9d-5ec2-8bae-a51c243ebd4c-4658006.jpg.